We’ve been prompted to write this blogpost following various recent conversations in which people have interpreted our call to change the public narrative around social care as one of adopting a ‘positive story.’ People say to us that they recognise the importance of conveying the good things that social care does, but that ‘we still need to speak truth to power and lay out the scale and urgency of the problems we face’.

To clarify, #SocialCareFuture’s primary goal isn’t to make the public feel more positive about social care. It’s to shift mindsets and grow expectations about how we should all be able to live our lives when we have reason to draw on support, the role support should play therein and how it needs to be resourced and reorganised to do so. It’s about firing people’s imaginations and opening up what Geoff Mulgan has called ‘the possibility space’ that permits us to see beyond the present and contemplate alternative futures.

It comes from a goal of wanting to move beyond our existing system, too much of which is under-resourced, under-imagined and poorly organised, meaning that the quality of people’s lives falls far short of what most of us would anticipate as even the very basics. Our theory of change is that the cultivation of a story of what social care at its best can and should be, and growing support for that, not only offers something desirable for people to get behind, it also reveals even more vividly the shortcomings and injustices of the status quo and helps make more people care about addressing it.

It’s about ideas, not language

The function of reframing or narrative change in our work isn’t to build a ‘positive story.’ It’s about ideas and is about changing the story or stories we carry in our minds when we hear or are prompted to think about social care, the values these bring to the fore and the feelings they generate. That’s because what we think and feel about a given issue guides the degree of importance we attach to it, how we understand causes, solutions, who we see as responsible for implementing the, and what we ourselves feel compelled to do about them. Whether a story is ‘positive’ or ‘negative’, these questions of framing remain crucial if we want to take people on a path of understanding that matches our own about what is needed to make change happen and ignite the values that are likely to help command the greatest support to do so.

Take for example the Joseph Rowntree Foundation’s work to reframe poverty, in partnership with the Frameworks Institute. Their work to map current discourse and thinking had found that poverty was often seen as a matter of fate, or lack of effort, down to the individual. Social security was regarded as the policy problem, with welfare reform centred on constraining spending by rooting out ‘skivers’ from ‘strivers’, again feeding from attitudes to poverty which failed position it as an systemic rather than individualised issue. In their reframed narrative, they talk about poverty as being caused by, among others external factors, ‘strong economic currents’ that ‘pull people down’, and of social security as ‘offering a lifeline’ and helping people to ‘stay afloat’. These reframes avoid triggering existing thinking, using powerful visual metaphors both to offer a different path of understanding and to ignite more supportive values around justice and compassion. JRF have demonstrated how this same framing can be used in the context of describing problems and their causes, as well as advocating solutions. A crucial lesson for those concerned with social care is the way JRF’s framing repositions a reformed social security system as part of the solution, not as *the problem* to be fixed.

Similarly, the Health Equals campaign supported by the Health Foundation is trying to gain increased focus and resource commitment to address the ‘social determinants of health.’ Following extensive research with the Frameworks Institute, the Health Equals campaign has adopted the metaphor ‘the building blocks’ of health, among other framing elements, as a way to build understanding about and attach importance to acting on the factors which shape our health and which predict health inequality. Again, this framing permits the Health Equals campaign partners to talk about both problems and solutions while building understanding and commanding support for action.

And in the animated short we shared last October we ‘dramatised’ the story by depicting what people today were losing as a result of failure to reform social care and what many more of us might face losing in the future.

As with the Health Equals and JRF work, the ‘negative’ relies on the same framing (that social care exists to support us all to live in the place we call home, with the people and things we love, doing what matters to us etc) as the positive, but flips it to focus on what is at stake by not reforming and investing in social care.

The sky is falling!

Balance is important, however, but it’s not between ‘positive’ or ‘negative’. Rather it’s between ‘urgency’ and ‘possibility’. Where a public narrative leans too far towards urgency, without offering possibility it risks generating fatalism and despondency. As the Frameworks Institute advise. “Crisis framing has, over time, caused a decline in public engagement and eroded people’s confidence in our civic and social institutions. As a result, the greatest communications task for most advocates these days is not to convince people that a problem exists; it’s to convince them that it can be solved.”

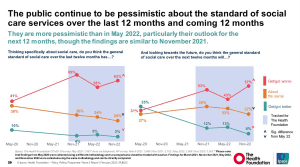

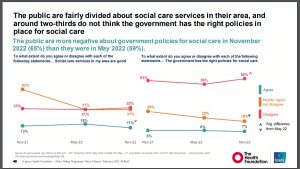

The alarm sounded by #SocialCareFuture to communicators in the field about their messaging is rooted in evidence that the public has over many years been fed and has internalised a story of social care that is solely about crisis, absent any sense of the value or possibility of resolving it. The repeated collapse of efforts to mount reform have further caused social care to be put in the box marked ‘too difficult’ by voters and politicians alike.

The challenging fact then is that the unremitting story of crisis shared by the sector and disseminated by the media, allied to the way social care is framed, is likely acting as an obstacle to increasing the salience attached to investment and reform by the public, and as a result, by politicians. There is a negative correlation: no one is left in any doubt there is a major problem, but they do doubt we are capable of resolving it, and each new report that emphasises urgency without offering possibility confirms that in people’s minds.

What our subsequent public audience research found, in developing an alternative narrative, is that a new framing, centred on a vision of what social care could be at its best simultaneously shifted understanding and feelings about social care while leading our audience to offer stronger support for investment and reform and increased optimism that it was possible.

Take action now

We don’t expect or advocate that organisations shouldn’t bring attention to the deep and persistent problems concerning social care. People need to understand what’s at stake. But if the way we communicate is to increase, rather than depress public support for investment and reform, it has to balance an account of what’s wrong, with what it will look like when we get it right, why people have reason to value that and a believable plan for getting there.

Moreover, it can and should remain faithful to framing which avoids the pitfalls of ‘othering’ or which provides people with no reason to value social care for themselves, their families or their community. Our research found that even the dominant narrative of crisis rarely says anything about the impact of resource scarcity on people’s actual lives, tending to elevate the impact on ‘the sector’, or workforce. Where it does say anything of people’s lives it will almost universally default to ‘letting down the most vulnerable in society’, which ‘others’ and as a result renders social care irrelevant in the minds of many.

So here’s a challenge to those people and organisations with plans to bring out ‘state of social care’ type reports over the coming months to follow 3 basic rules:

Balance urgency with possibility: start with a vision for how people should be able to live their lives as a result of social care, offer glimpses of a better future and explain how, through investment and reform, these could become more commonplace

People first: make it about people, families and our shared lives, not ‘the sector’. Explain how a failure to invest in and reform social care means more of us and the people we care about losing control over where and with who we live and unable to retain contact with the people and things that matter to us.

Avoid othering: do not say the problems faced by the sector are ‘letting down the most vulnerable in society’. Instead, talk about how they mean that ‘many of us will face losing control over our lives & contact with the people and things that make our lives worthwhile’.

We hope you’ve found this helpful, but welcome your comments and ideas!