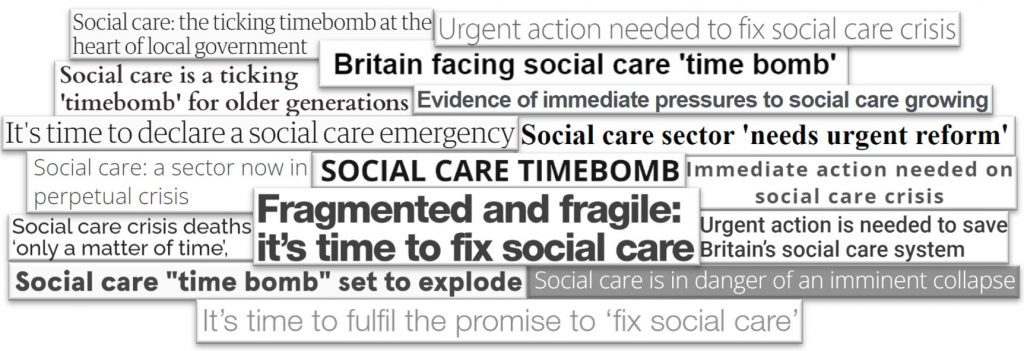

It feels like we’ve been talking about early action and prevention in adult social care, health and wider public services forever, largely to bemoan the fact that there is so little investment in and action around early action and prevention… A recent ADASS survey reported that the percentage of the net adult social care budget spent by local councils on prevention had dropped to its lowest level ever recorded, a paltry 6 per cent.

Can we break this impasse, and could reframing and narrative change play a role?

There are many things in life that we as humans put off, despite the well-known adage that ‘prevention is better than cure’ and being told of, or knowing deep down the consequences of doing so: taking more exercise, or adopting a better diet, spending enough time cleaning our teeth, saving for retirement, eliminating child poverty, action to avert climate change, telling somebody that we love them while we still can. We generally struggle to foresee or gauge the risks of delay, or to imagine or accept the future costs and consequences of things we are or are not doing now. This is especially so if they involve contemplating a future life we don’t want to imagine having to endure, or where we perceive costs or inconveniences in the present that outweigh concerns about our future selves, or when the future probability is of something that might happen, but also a reasonable chance it might not. We might feel we live in a pessimistic, hope free world, but most of us are actually eternal optimists. On the other hand, the state of the news may make many of us wonder why we should bother making any accommodations with the future, and like optimism, fatalism is not the ally of doing things today on the off-chance they might pay off down the line.

In public services like the NHS and adult social care, putting things off has got us caught in a doom loop: the less we focus on prevention, the more pressure there is on ‘acute’ services, the less time and money there is for prevention. As Dame Louise Casey said recently, the Department for Health and Social Care should be renamed the ‘National Hospital Service’ – as so little of its resource is focused on keeping people active, connected and well in their homes and communities, with little if any active focus on the building blocks of health and wellbeing across government. In adult social care ever tighter eligibility thresholds create the impression of adult social care as an emergency service. In turn, this gives people (and many informed policy makers) reason to believe that social care largely offers only ‘emergency’ solutions like residential care, and hence good reason to hold off until they can cope no longer. As a result, adult social care largely connects with people once crisis has taken hold and the opportunities to avert or delay it have too often been missed. Rightly or wrongly, it of often seen as in the business is ‘managed decline’, not as life affirming and enhancing. And if that’s the case, then what use prevention?

The system change needed to shift this is complex but I’ve felt for a while that one element of breaking free of this doom loop relates to how ‘prevention and early action’ are framed, imagined and understood. That’s what this post will now turn to.

The glue that binds

Last year we shared new research and advice on how to talk about adult social care, the product of work that #SocialCareFuture and partners led with Frameworks UK. This built on our earlier work to change the narrative. What lessons might that work – and wider thinking about framing in related fields – offer for how we talk about early action and prevention?

I think ‘early action and prevention’ distils a wider perceived tension that plays out in all messaging around adult social care, much of which is directed only at policy makers and those managing the public finances, or tasked with managing throughput. As a result it is often solely in the technical policy language of reducing pressures, managing demand and making savings, positioning ‘the system’ as the protagonist of the story, not people and families seeking support. Further, the accent is overwhelmingly on those pressures that are being experienced by NHS managers (and more specifically, hospitals) not by adult social care. A thicket of impenetrable language has then emerged around this technical notion of prevention as keeping people out of hospital: DTOC, discharge to assess, hospital to home, crisis-response, frequent flyers, all of which reenforce the perception of prevention as being fairly last ditch: the bit that happens just before the hospital waiting room.

Do these messages help build understanding and consent from the wider public for investment in early action and prevention, and how do they shape mindsets about the value, purpose and nature of action and activity falling under this heading?

If prevention is framed as a way to avoid providing care in future, might people intuit it as withholding support from people who need it? Might such a message fuel stigma about seeking care or support, generating a sense of personal failure or shame which in turn makes it even harder to reach people earlier? When the measure is promoting ‘independence’ versus ‘dependence’ this seems a real risk. This is also a particular risk of the way talk of prevention remains so often through a health lens and focused on the consequences of personal behaviour – as about making better choices – rather than the impact and outcomes of systems, environments, and support.

Moreover, given how little evidence there is of a shift to prevention in the way councils spend adult social care budgets, or of NHS funding being redirected to adult social care, we have to ask whether, as presently framed, such messages actually work in mobilising policy makers and those making financial decisions to support early action and prevention, whether within existing parameters or to imagine moving beyond them.

Again, the primary accent on health (and ‘protecting the NHS) isn’t helping. Prevention is often assumed to be about screening, lifestyle choices, medicine and therapy, with the social determinants- like good housing, a living income, access to nutritious food – largely missing from the discussion. Even when talking about prevention, social care is rarely, if ever, characterised as one of the building blocks of health and wellbeing, only as a (faulty) pressure valve for hospital ‘flow’ and capacity.

Meanwhile, prevention is justified with long term logic, but judged against short term results. It requires patience, yet this is rarely ever named or defended publicly. Pilot initiatives aren’t of sufficient scale or duration to generate the evidence of durable shifts, and evidencing them is fraught with challenges. This is especially so when claims made about what ‘prevention’ can achieve are misleading. Prevention is often sold as a cost-saving silver bullet, but people working in the system know savings can be slow, partial, or non-cashable. Rather, prevention needs to be framed as smart investment, that involves redistributing spending to use resources more effectively and productively while helping to reduce risks, volatility and increase predictability. Doing so can lead to cost-avoidance of course, but it isn’t the sole purpose or value of prevention and early action, and focusing only on cost-avoidance can lose public and policy audiences alike.

I want then, based on the research we commissioned and that developed by others, as well as general good practice, to suggest three broad shifts in the way we talk about early action and prevention as it relates to adult social care (and more broadly) that might help to shift the debate and open up the possibility space for change:

- Frame prevention and early action first and foremost as a collective social good with the system serving people, not as technical policy serving the interests of ‘the system’

- Focus, both to the public and policy makers, on the ‘costs of delay’

- Shift the financial argument from ‘savings’ to good stewardship

Framing prevention and early action as a collective social good

As Anat Shenker-Osorio always advises “Sell the brownie, not the recipe… So instead of taking your public policy out in public and thinking that that is a message, which it is not, you talk about the outcome of your policy.”

What are the outcomes from prevention and early action we are looking for, that everyone has reason to value? From a ‘gain’ perspective it is about being able to:

- stay living in our own home

- keep relationships going

- remain active and involved

- stay in control

- feel confident and secure

From a ‘loss’ perspective, it is about helping us to avoid

- isolation

- crisis

- breakdown of family support

- losing control

Applying the rules of our wider framing work, of speaking to shared universal values and avoiding othering, we might use this opening frame:

“We all want life to keep working when things change — to stay living in the place we call home, connected to the people and things that matter to us. Early action prevents our lives coming apart.”

Or we might say:

“Right now, support often comes too late. Strengthening early action means people live well for longer and crises are avoided.”

This is also where the metaphor from our research of social care as the ‘glue that binds’ can come into good use:

“Social care acts the glue that helps us to hold our lives together when things change. Early action strengthens that glue before pressure builds.”

As with our general advice on framing social care, building understanding of how this works, what it means in practice and the solutions available is crucial. Prevention and early action might involve things like:

- Making our homes safe, comfortable and easier to live in

- A bit of extra help around the home

- Support to stay active and connected to the people, places and things that matter to us

- Counselling and emotional support

Real-life examples of the above help bring them to life and build confidence in them.

The cost of delay

Too often the question asked around prevention and early action is ‘can we afford to invest now?’ Instead, we need to pose the question ‘what will delay cost us?’

We might say:

“Delaying support doesn’t save money — it shifts cost into the most expensive parts of the system.”

“Right now, we often wait too long to act in social care — and people pay the price. Early support keeps life connected and prevents avoidable crisis.”

And we need to spell out what delay equals:

- higher than desired numbers in residential care

- longer waiting lists for social care assessments

- more emergency admissions

- longer hospital stays

- family and carer breakdown

- workforce withdrawal

- higher long-term dependency on more expensive support

The glue metaphor also works well in positioning the role social care can play in avoiding the costs of delay across public services without feeling compelled to talk about prevention through the lens of health:

“Social care is the glue that holds the system together. When the glue is weak, pressure shows up elsewhere — in hospitals, housing, and crisis services. Strengthening it early stabilises the whole system.”

This avoids the problematic “social care props up the NHS” framing, while still explaining interdependence, something important in discourse with both the public and policy-makers

From ‘savings’ to ‘good stewardship’

As outlined above, the Treasury, as well as finance people in local councils and the NHS, can be sceptical when we make arguments that are about crude cost reduction, savings or cutting demand, and often the challenges we face in evidencing these claims see support for change ebb away.

Instead, we might talk about protecting existing public investment, reducing expensive crisis responses, addressing avoidable costs, making better use of public resources and investing earlier to prevent higher downstream costs. For example, we might say:

“Early action protects the value of existing public investment by preventing avoidable crisis later on.”

Or

“When support comes early, people stay connected and well. When people stay connected and well, families cope better and crises are less likely. When crises are avoided, we reduce the most expensive forms of public intervention.”

Crucially we might reframe early action not as saving but as spend rebalancing:

“This is not about spending more overall — it’s about spending earlier, more predictably, and more effectively.”

And we can spell out, with evidence, the operational benefits for system leaders:

- fewer crises

- better flow

- more predictable numbers seeking support

- less staff burnout

- better planning certainty

- reduced emergency escalation

For example:

“Early action makes pressure more predictable and manageable — which is exactly what system leaders need.”

And for all audiences, we need to frame early action and prevention not as cuts and savings but as good stewardship.

Some lines to take

How can we boil this down into pithier lines to take, in media interviews, meetings, speeches, social media posts, or even a 30 second ‘elevator speech’? Here are some initial suggestions but you can come up with your own:

“Support that starts early helps people live well for longer.”

“We wait too long to act in social care — and people pay the price. Early support keeps life connected and prevents avoidable crisis.”

“Early action in social care keeps lives working and keeps our health and care systems stable. It reduces crisis, volatility and avoidable cost — while delivering better outcomes for people and families.”

“When support comes early, life stays connected. Early action in social care strengthens the glue that holds life together, helping people live well for longer and reducing avoidable crises.”

“Early action in social care isn’t about doing more sooner — it’s about keeping people connected and supported before problems escalate.”

“Social care is the glue that holds life together. Strengthening it early helps prevent lives coming apart later on.”

“Early support helps people adapt as life changes. That means stronger families, better wellbeing, and fewer emergency situations down the line.”

“Early support keeps life together.”

“Early action in social care = stronger connections, better lives, fewer crises.”

Conclusion

We welcome your thoughts.